Keeping Track of Time Zones

| By Richard N Williams

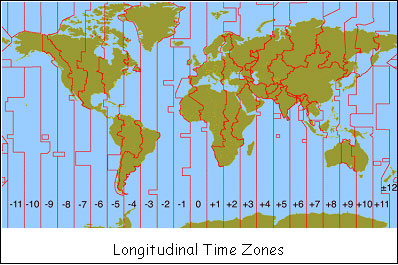

Despite the use of UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) as the world’s timescale, time zones, the regional areas with a uniform time, are still an important aspect of our daily lives. Time zones provide areas with a synchronised time that helps commerce, trade and society function, and allow all nations to enjoy noon at lunchtime. Most of us who have ever gone abroad are all aware of the differences in time zones and the need to reset our watches.

Keeping track of time zones can be really tricky. Different nations not only use different times but also use different adjustments for daylight saving, which can make keeping track of time zones difficult. Furthermore, nations occasionally move time zone, normally due to economic and trade reasons, which provides even more difficulties in keeping track of time zones.

You may think that modern computers can automatically account for time zones due to the settings in the clock program; however, most computer systems rely on a database, which is continuously updated, to provide accurate time zone information.

The Time Zone Database, sometimes called the Olson database after its long-time coordinator, Arthur David Olson, has recently moved home due to legal wrangling, which temporarily caused the database to cease functioning, causing untold problems for people needing accurate time zone information. Without the time zone database, time zones had to be calculated manually, for travelling, scheduling meetings and booking flights.

The Internet’s address system, ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) has taken over the database to provide stability, due to the reliance on the database by computer operating systems and other technologies; the database is used by a range of computer operating systems including Apple Inc’s Mac OS X, Oracle Corp, Unix and Linux, but not Microsoft Corp’s Windows.

The Time Zone Database provides a simple method of setting the time on a computer, enabling cities to be selected, with the database providing the right time. The database has all the necessary information, such as daylight saving times and the latest time zone movements, to provide accuracy and a reliable source of information.

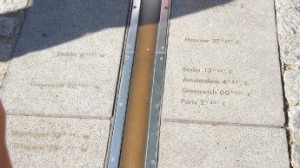

Or course, a synchronised computer networks using NTP doesn’t require the Time Zone Database. Using the standard international timescale, UTC, NTP servers maintain the exact same time, no matter where the computer network is in the world, with the time zone information calculated as a difference to UTC.

Researchers have discovered that the British atomic clock controlled by the UK’s National Physical Laboratory (

Researchers have discovered that the British atomic clock controlled by the UK’s National Physical Laboratory (

The service, available by dialling 123 on any BT landline (British Telecom), began in 1936 when the General Post Office (GPO) controlled the telephone network. Back then, most people used mechanical clocks, which were prone to drift. Today, despite the prevalence of digital clocks, mobile phones, computers and a myriad number of other devices, the BT speaking clock still provides the time to 30 million callers a year, and other networks implement their own speaking clock systems.

The service, available by dialling 123 on any BT landline (British Telecom), began in 1936 when the General Post Office (GPO) controlled the telephone network. Back then, most people used mechanical clocks, which were prone to drift. Today, despite the prevalence of digital clocks, mobile phones, computers and a myriad number of other devices, the BT speaking clock still provides the time to 30 million callers a year, and other networks implement their own speaking clock systems. Consisting of a 300kg gear wheel and a 140kg steel pendulum, the clock will tick every ten seconds and will feature a chime system that will allow 3.65 million unique chime variations—enough for 10,000 years of use.

Consisting of a 300kg gear wheel and a 140kg steel pendulum, the clock will tick every ten seconds and will feature a chime system that will allow 3.65 million unique chime variations—enough for 10,000 years of use.